Why the Pandemic is Destabilizing Us So Profoundly: The Cardinal Mistake of the Cognitive Miser

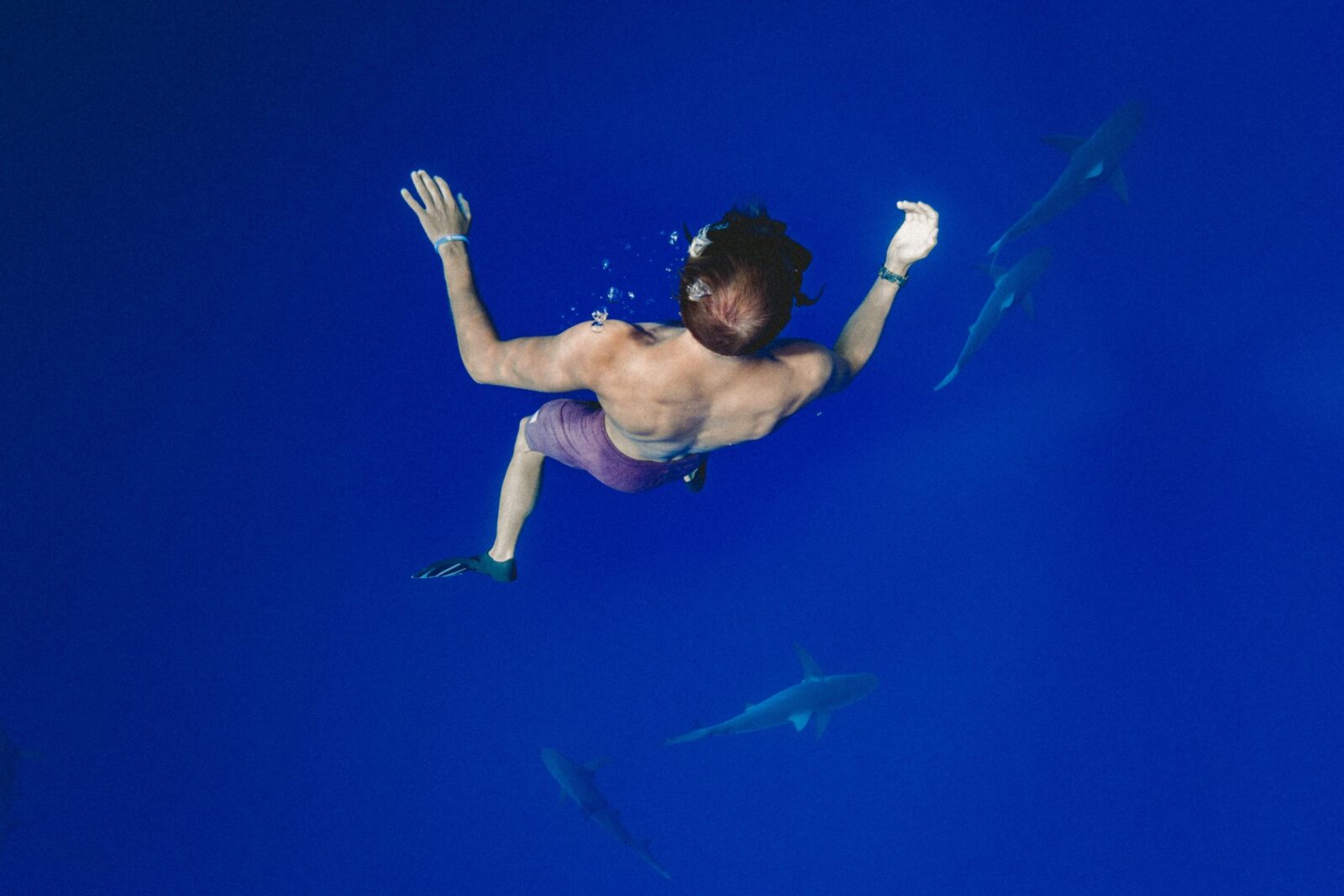

When asked what they most fear, being killed by a shark or dying in a traffic accident, most people reply that they are more afraid of the former.

Let’s consider the numbers: according to CDC data, every year about 1.35 million people die worldwide in traffic accidents, or about 3,700 per day. In 2019, two people worldwide were killed by sharks. The global average is about four per year. This means that, in a typical year, your chances of being killed in a traffic accident are 337,500 times higher than being killed by a shark. (Incidentally, you are over 37 times more likely to be killed by a falling coconut than a shark.)

Yes, But It’s a Shark

These numbers notwithstanding, you’re still probably more afraid of a black fin cutting through the water in your direction than a motorist swerving across a median toward your car. Why is our fear so irrational? One of the most agreed-upon, central findings of social psychology is that human beings tend to engage in an automatic and unconscious processing of social information.

Why do we do this? We act as “cognitive misers” (i.e., have preference for simpler, less effortful solutions) and conserve our finite internal cognitive resources (e.g. attention and energy for information processing) in order to adequately handle life events as they come along.

One way in which we conserve our finite cognitive resources is the availability heuristic. This cognitive bias is our tendency to believe that images we can bring to our mind quickly are more representative of objective reality than they actually are. Let’s consider two examples of the availability heuristic at work.

Exhibit A: as previously mentioned, shark attacks. George Burgess, director of the International Shark Attack File housed at the University of Florida’s Museum of Natural History, explains this cognitive bias well: “The danger of a shark attack stays in the forefront of our psyches because of it being drilled into our brain for the last 30 years by the popular media, movies, books and television, but in reality the chances of dying from one are infinitesimal.”

Exhibit B: the pandemic. Conserving our cognitive resources has become that much more challenging as most of us are learning for the first time how to think during a pandemic. With images of the effects of COVID-19 flying fast and furious on social media 24-7, it’s like stumbling into a movie theater in 1975 playing Jaws and being unable to leave. (There is some irony in that, forty-five years later, we both the captives and our own captors.)

The Role of Uncertainty

Why are we so captivated? To help us find an answer, consider this story. About nine years ago, a friend was sitting in a restaurant with his wife in a small town in France and he noticed that almost everyone in the restaurant was looking at their smartphone. It was novel and, for that reason, caught his attention. Today, this story is no longer a story: it’s what we witness just about every time we go out—when we used to go out, that is. Sharing this story today is like recounting that you went to a baseball game and observed the fans standing up and cheering. What’s not new is not news.

Habituation is the enemy of our natural human tendency to misrepresent reality with what we can more easily imagine. In addition, we have a natural human tendency to focus more attention on negative than positive events and situations. I’ve interviewed hundreds of people in organizations about how their leaders express their emotions and its effects on them and have found that the role of novelty can be even more important than the attention-drawing effects of negative emotions.

An army lieutenant I interviewed, for example, recounted how his commander used to shout at him and his other squadron members so often that they just tuned him out. “It was just him yelling,” he shared. Then his commander’s superior was replaced by a much more mild-mannered individual who asked his commander to work on better controlling his emotions. The reaction of his squadron was quite different once his commander’s expression of negative emotion became novel. According to the lieutenant, “Because [now] he controlled his emotions so much, when we started to see swings in his emotions, it bothered everybody…When someone who never yells starts screaming, then people pay attention, they get a little bit afraid.”

So there is a high degree of uncertainty associated with COVID-19, and as a result we are more than a little bit afraid. To reduce our uncertainty—exacerbated by myriad interpretations of everything going on around us shared on social media every second—it is more critical than ever that we sift through the digital morass for true facts to make sense of the world. Going against our propensity to act as cognitive misers, we must focus on facts, not feeds. We can then use these facts to make well-thought-out, judicious decisions about how we will go about our lives.

How do you manage uncertainty during the pandemic? How do you stay “in the know” while maintaining a sense of inner peace rather than being glued to news feeds 24-7? Please share your experiences with us in the comments.