What Rodney King, Eric Garner and George Floyd Have in Common

Many people do not understand the real reason the recent police murder of George Floyd has incited such widespread rage, civil disobedience and disenfranchisement from our government and political system.

Let’s take a closer look at the death of Eric Garner. Like Floyd, Eric Garner, a 43-year-old African-American man and father of six, gasped “I can’t breathe” eleven times before suffocating in a police chokehold in Staten Island on July 17, 2014. His alleged crime? Selling loose cigarettes.

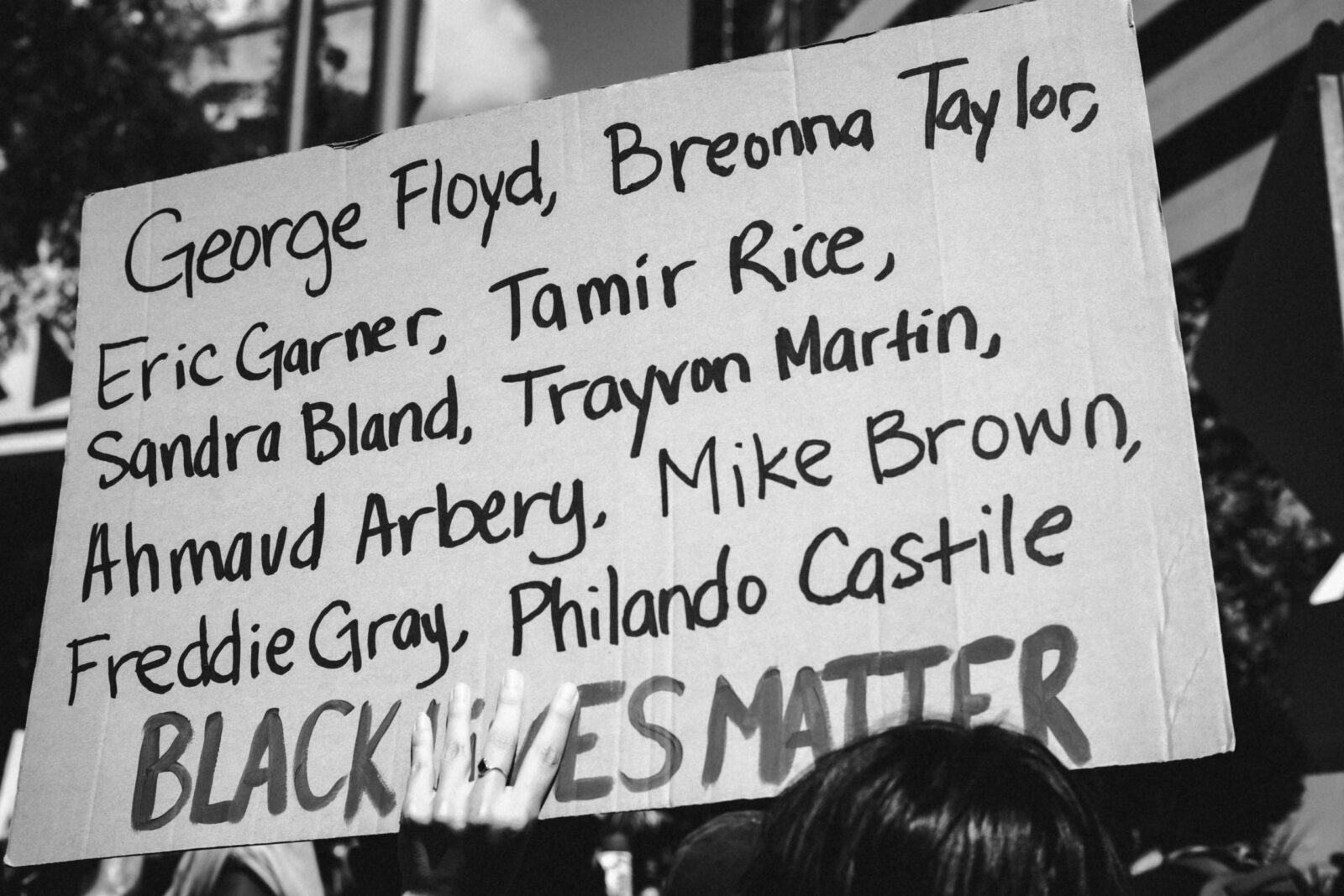

Like George Floyd and Rodney King, Eric Garner’s murder moved the nation to action. Why? What do these three abhorrent incidents share in common? Collective complicity: each incident is characterized by not one malevolent police officer acting alone, but a manifestation of systemic racism rooted in the dehumanization of African-American men.

Yet in many ways, the Garner tragedy most exposes how these watershed stains on our nation’s history exposed systemic racism. Not only did the police officers who arrested Garner along with Daniel Pantaleo—like the officers who accompanied Chauvin—not come to the victim’s aid during the lengthy act of violence, but neither did the two paramedics or two emergency medical technicians dispatched by the Staten Island Hospital.

When the health workers arrived at the scene at 3:36 pm, one said to Garner, “Sir, it’s E.M.S. We’re here to help you. We’re getting the stretcher, all right?” Garner did not respond. A bystander asked why they weren’t trying to resuscitate him, and an officer replied because Garner was breathing.

Court documents revealed that “The E.M.T.s did not conduct the appropriate examination” and “failed to provide [Garner] with the necessary lifesaving procedures.” The message, internalized by millions of African-Americans nationwide and fueling the exponential growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, was, once again, that black lives don’t matter.

In my interviews with over 250 officers and staff in ten police departments nationwide on how they manage trauma, I have discovered that one common issue police grapple with daily is that the public either perceives them as heroes (e.g., after 9-11) or villains (e.g., after Eric Garner)—with no in between. The reality is that most police are our front-line civil servants, out on the streets every day attempting to keep us safe.

The words of an officer I interviewed last year are a reminder of their courage they have to muster up daily to put themselves in harm’s way for the rest of us:

If for some reason, I were to die in the line of duty, I think that’s a lot more valiant for my daughters to know that I was a brave man and exemplified that than to [die] in a hospital bed … I’d rather … have my daughters be proud of [me].

Just as we should not judge African-American men before (the roots of the word “pre-judice”) taking the time to sit down with them and hear their stories and motivations, neither should we men in uniform. Most police are as angry with Chauvin and his fellow officers as you or I am, if not more: thanks to the actions of these Minneapolis cops, the setback to their occupation and the legitimacy of law enforcement is immeasurable. It is for this reason that numerous police officers recently kneeled in several US cities in solidarity with protesters.

Consider: After the killings of Eric Garner and, four months later, Tamir Rice—a twelve-year-old African-American boy lethally shot by Cleveland police for brandishing a fake gun despite the caller warning that the gun was “probably fake”—the disparity between the perceptions of police as honest and ethical among whites and non-whites widened tremendously. According to a Gallup poll, between 2013 to 2014 there was virtually no change in white perceptions (58 to 59 percent) while perceptions of police as honest and ethical decreased from 45 to 23 percent of the African-American population during the same period.

Clearly, the ruthless act of Chauvin and the apathetic behavior of his white and Asian colleagues, during almost nine excruciating minutes of a man writhing in clearly heard yet unacknowledged pain, has undone so much of the progress that innumerable individuals have worked so hard to create since the heinous acts of half a decade ago.

What we still don’t understand is what it feels like to be promised a system that will treat all people fairly as human beings—where, as Martin Luther King, Jr. once shared, each individual “will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character”—and then to be spit on in the face.

What is at stake now—not just for African-Americans but also for the legions of people of all ethnicities who have joined with them in nonviolent civil protest—is trust. We all need to believe that Dr. King’s vision can still become our reality, and that this system—with some major work and commitment—can become equitable toward all people, independent of their ethnic, gender or cultural backgrounds. Otherwise, this great nation is not worth living in.

Locked inside the better part of this past three months, it has been my deepest hope that the pandemic will become a giant reset button for many of us: a chance to start over, to emerge from our homes with a different and more sustainable approach to going about our lives. The tragedy in Minneapolis illustrates that, for some, this will not be the case.

As a good friend of mine, Cheryl Dorsey, president of Echoing Green, a global nonprofit that supports emerging social entrepreneurs, recently wrote, “The only word that makes sense to describe the pain so many African-Americans feel at this moment is ‘familiar.’ The pain is so familiar because its cause is so relentless. It invades our families, our hopes, and our dreams.”

Another friend, a senior corporate executive, shared with me a few days ago:

One reason we are losing our minds right now is that we have been fighting for this for so long and the recent incidents show that there is still a segment of the country that hates black people and still doesn’t see us as human. This country was built on systemic racism. What is at stake is the dream that we can be equitable as my generation is getting tired and more angry. I am a covert angry black man.

Yet the massive outpouring of civil disobedience exhibits the potential for this change within each of us. Viktor Frankl, the Austrian psychiatrist who survived four Nazi concentration camps, once wrote “Live as if you were living a second time, and as though you had acted wrongly the first time.”

This redemption is possible. The opposite of forgiveness is resentment, a word derived by the Latin roots for feel and again. Resentment is to feel anger over and over and over again, which succeeds only in paralyzing us.

This resentment is not going anywhere fast—especially for the untold number of people who have been stuck in their homes for the past three months and are now afraid to leave. Yet in parallel, we must slowly begin to believe again, undaunted. Over time, we must align our beliefs with concerted action and internalize Dorsey’s inspiring words:

The protests represent a beautiful, full-throated demand for full citizenship by … marginalized groups in this country. This shows us that they have not forsaken our grand democratic experiment but rather are willing to fight hard to be a part of it. In a moment of fracture and division, take heart in that. I am so grateful that they have not given up on the idea and ideal of America.

Amen.

How are you handling your resentment over the tragedy in Minneapolis? What actions are you taking so George Floyd will not have died in vain? How will you apply your learning to produce positive change in our society? Please let us know in the comments so others can benefit.